I, Ananya Bhattacharya, had the privilege of reading Heart Lamp, a powerful collection of stories by Banu Mushtaq, and it has left me both moved and disturbed. As a woman, reading the stories of systemic gendered oppression layered with communal complexities was not just an intellectual exercise—it was emotional and visceral. These are stories that refuse to look away, and in reviewing this book, I feel a deep responsibility to give voice to what they illuminate.

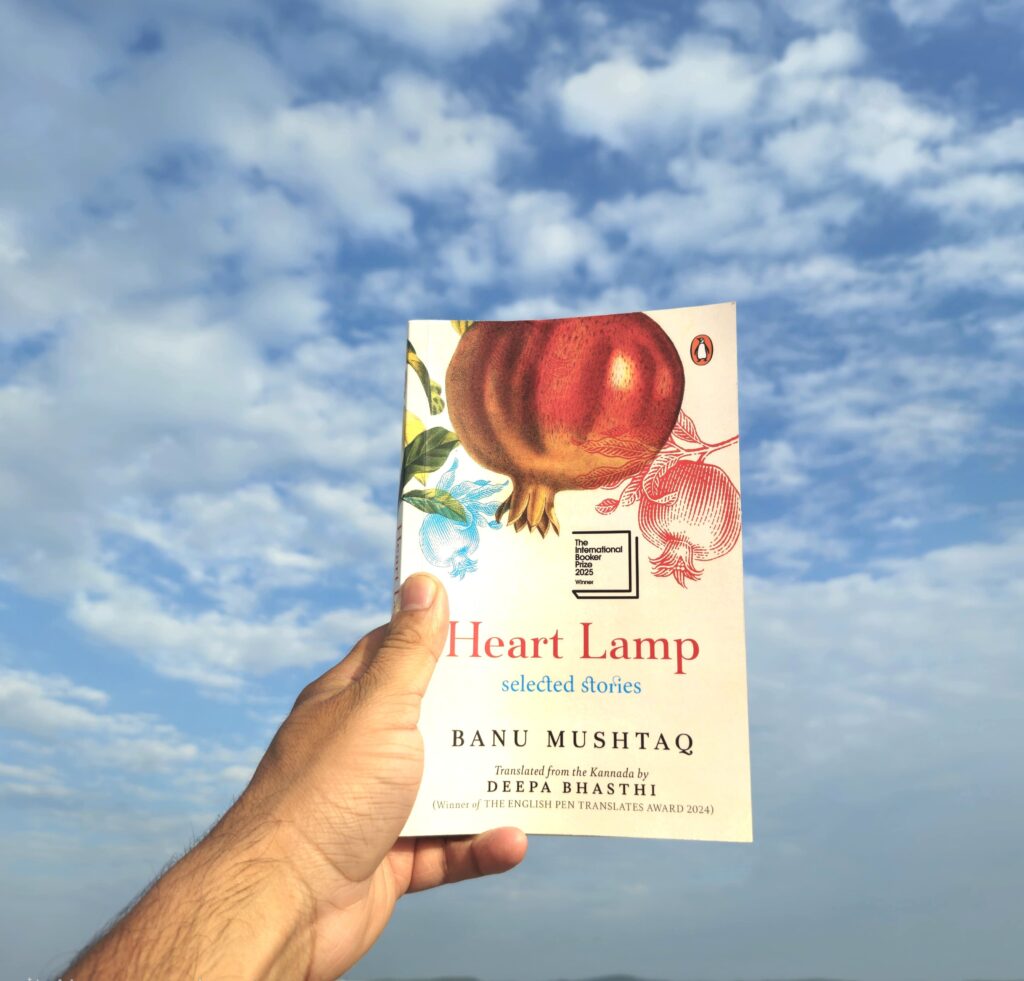

Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp is not merely a collection of stories—it is an act of resistance, a literary embodiment of bandaya, a Kannada word that translates to rebellion, dissent, and protest. Emerging from a tradition that challenged the patriarchal, upper-caste stronghold on Indian literature, it emerged from a lineage of resistance against dominant, patriarchal, upper-caste, male-centric narratives. Mushtaq’s writing is soaked in the lived realities of Muslim women in small-town Karnataka, and her characters do not exist in abstraction—they breathe, suffer, and survive within the tangled webs of family, religion, and class. Her voice joins the ranks of radical women who have redefined storytelling by weaving the personal and the political into inseparable strands.

The translator’s note, as layered as the stories themselves, acknowledges the complexity of this task: a lapsed Hindu and upper-caste translator rendering a minority woman’s voice into English. Yet this very positionality, when held with care, as it is here, yields a deeply conscious translation. There’s a reverence for the rhythms of language, for the multilingualism that defines both Mushtaq’s stories and the cultural reality they emerge from. Words in Kannada, Urdu, and Arabic are left untranslated and unitalicized—a bold editorial choice that de-exoticises them, asserting their legitimacy within English prose.

Each story in Heart Lamp pulses with its own emotional and political weight. In “Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal,” the domestic becomes a battlefield. Shaista’s quiet endurance, her veiled defiance, speak volumes about the emotional labour women shoulder in the name of harmony. The story’s most jarring moment comes not with physical violence, but in the stifling silences Shaista is expected to occupy.

“If your mother dies, it is the death of your mother’s love too. You will not get that kind of love from anyone else. Huh. But if the wife dies, it is a different matter, because one can get another wife.”

“Red Lungi” is simultaneously tender and provocative. It probes the sensuality and agency of a woman who dares to desire—and in doing so, it unsettles. For me, this story brought an almost physical discomfort. To see a woman’s body treated with a transactional coldness by those around her, even while she tries to reclaim it, was deeply affecting.

“Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord”, probably my favourite story from the collection, felt like a cry of exhaustion. The protagonist’s plea is not for radical change, but for respite—a moment of peace in a life governed by obligation and patriarchal scrutiny. The story’s religious and philosophical undertones are subtle but sharp, challenging not just social norms but the theological frameworks that sustain them.

“A Taste of Heaven” offers a deeply ironic title for a story steeped in hunger—physical, emotional, and spiritual. It explores the hierarchy within domestic households, where food becomes a tool of both control and compassion. The protagonist’s yearning is not just for aab-e-kausar but for her long-suppressed youth, for the smallest acknowledgement of her existence. What struck me most was how Mushtaq uses something as mundane as a Pepsi drink to expose the layers of societal expectations on a woman.

These stories do not offer resolution. They’re not meant to. And that’s where their strength lies. Mushtaq doesn’t hand us neat narratives of liberation or redemption. Instead, she gives us women who persist. Who endures. Who speaks in codes, in gestures, in silences. Their resistance is often quiet, but never passive.

As someone who has grown up with the contradictions of modern womanhood in India, where freedom is often performative and safety conditional, reading these stories felt personal. The cruelty of small compromises, the routine indignities of gendered life, the inherited obedience that masquerades as tradition—all of it hit too close to home. At times, I had to pause, look away, and breathe. There were far too many times when I was tempted to leave it halfway—but something about the writing, the urgency behind the words, the silent screams of the women in the stories, a naked representation of that class of society who are used to being unheard and neglected, unsettled me. And so, every time I was hit with disgust and rage, I also reminded myself to be grateful for a life most of these protagonists would die wishing for.

What adds further richness to this collection is the translator’s insistence on preserving orality. Mushtaq’s prose mimics speech: tenses shift, phrases repeat, thoughts interrupt each other. It’s not messy—it’s lived. Language here becomes both a map and a mirror.

The acknowledgements from both Mushtaq and Bhasthi underscore the collaborative nature of this work. They remind us of the quiet communities behind every story, this journey is probably theirs. The translator credits friends and collaborators who helped shape the linguistic fabric of the book, while Mushtaq offers a simple thank-you to her husband. That line struck me—how even in the life of a woman writing bravely, there may be someone quietly supporting her from behind the curtain. Their combined efforts have brought these stories to a global audience, culminating in the prestigious International Booker Prize recognition.

Heart Lamp is not an easy read, nor is it meant to be. It unsettles with its honesty. It doesn’t perform resistance—it embodies it. For those willing to sit with its discomfort, it offers an unparalleled window into lives too often ignored or misunderstood in Indian literature.

This collection is essential reading—not because it gives us answers, but because it forces us to ask better questions. About who gets to speak, and who listens. About what it means to be a woman in a world that demands endurance more than expression. The book is a blatantly harsh reality of many women, their existence reduced to being caretakers of their family and to reproduce male offspring and forgotten/replaced as soon as their purpose is served. In a literary landscape that still struggles with inclusion and representation, Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp doesn’t just claim space—it illuminates it.

No responses yet